ACTION reference to an INSIDE HOUSING magazine piece dated 01 May 2009. VERY TELLING insight on how Tory London has been ADDING NEW POVERTY

0400 [0340] Hrs GMT

London

Friday

18 march 2011

By © Muhammad Haque ...

Yesterday’s London EVENING STANDARD’s denunciation of Karen Buck, MP who is also one of Ken Livingstone's ‘mayoral candidacy campaign team members’ [2012], is very timely reminder of where the DISPOSSESSION-creating journalism is heading.

The EVENING STANDARD WANTS MORE DISPOSSESSION in London, not less. And the Karen Buck ‘tactics’, AS REPORTED by the EVENING STANDARD, will make things even worse for people in areas like Tower Hamlets unless she and anyone else who may actually want to stop the Tory attacks on the low income sections of the population get a fast grip of the so-called ‘evidence’.

Evidence that Tories like ex MP [CON] Marion Roe’s daughter Phillipa Roe [Housing chair, City of Westminster and one of the most Right-wing ‘local’ Councillors to be found anywhere in the UK today] have been abusing in their promotion of internal deportation of people already denied basic equality of income and all that goes with income parity.

The ‘tactics’ that Karen Buck has used are false, as they really rely on the emotion of the matter rather than the substance. She should go for the substance and concentrate her energies on showing the truth of HOW the Tories are CREATING POVERTY by using Housing as they have been for the past three years of the reinforced propaganda bandwagon following the take-over of ‘the Onion’ by the truly Right-wing brigade brought in by Boris Johnson.

We shall be detailing the REVERSE of the Tory Right Assault in London via Housing and show just how inept and useless the so-called Official opposition on the London Assembly has been about Housing.

And about CREATING NEW POVERTY via Housing.

[To be continued]

The new blue

01/05/2009

Print

Email

Share

Comments (4)

Save

Twelve months on from Boris Johnson’s election as London mayor Tory politicians are stamping their mark on the capital. Crispin Dowler meets the key players and discovers the national significance of their housing policies.

Boris Johnson’s election as London mayor – a year ago this week – marked a tidal shift in the political character of the capital. That day made Mr Johnson the first Conservative in the role and one of the most powerful Tories in the country. It also made him one of the most powerful figures in housing.

He inherited from his Labour predecessor, Ken Livingstone, sweeping new powers to decide major planning applications, and major influence over the city’s £5 billion housing budget.

For Conservative boroughs, this was a dramatic reversal of fortune. Mr Livingstone’s mayoralty had been marked by wars of attrition over housing between City Hall and Conservative councils like Hammersmith & Fulham. The former mayor thought Tory councils were reluctant to provide new social homes, and would not do so without pressure. The boroughs countered that his centrepiece policy – that half of all new homes should be affordable – impeded development.

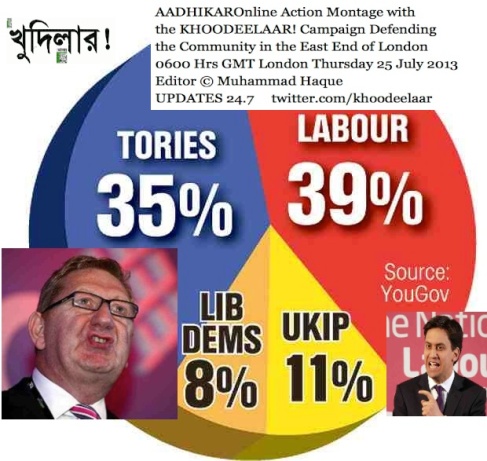

But the significance extends beyond London. A post-Budget YouGov/Daily Telegraph poll put the Conservatives 18 points ahead of Labour. With the prospect of a Tory government looming large, the symbolic importance of a Conservative-controlled capital is not lost on the national party.

For anyone keen to know what the next government’s housing policy might be, London has become the Petri dish to examine Conservative power in the 21st century. The mayor’s pledge to abolish the 50 per cent target closely mirrors the animosity to planning targets in the party’s new housing manifesto. And beyond City Hall, London is culturing the spores of a radical new Conservative housing politics. Last week Stephen Greenhalgh, the influential leader of Hammersmith & Fulham council, published a blueprint for sweeping deregulation of social housing.

Now, on the first anniversary of Mr Johnson’s election, Inside Housing meets three figures at the heart of London’s new Conservative housing experiment.

The mayor’s advisor

Richard Blakeway, director of housing at City Hall

It might not have happened as often as he’s had hot dinners, but Boris Johnson has been described as ‘inimitable’ more than most. Meet his chief housing advisor and you might begin to question the wisdom of that tag.

Many have commented on Richard Blakeway’s uncanny similarity to his boss. Both men present a near-caricature of the dishevelled public schoolboy: all well-fed vowels, unkempt manner and captain-of-the-debating-society enthusiasm for political argument.

Both are also willing to court controversy for the sake of a snappy line.

Earlier this year, while arguing that quality of life for social tenants is a ‘joke’, Mr Blakeway claimed ‘46 per cent of social tenants on estates love their dog more than their neighbour’. His speech prompted the late Defend Council Housing chair Alan Walter to call for him to be put on a lead.

The story of how 30-year-old Mr Blakeway became director of housing at City Hall offers a useful insight into the mayor’s relationship with David Cameron’s Conservatives. Before joining the mayor’s campaign, Mr Blakeway’s entire professional life had been in Westminster, working his way from researcher to policy wonk. When Mr Cameron became Tory party leader in 2005, Mr Blakeway was appointed to an 18-month review of international development policy, alongside Sir Bob Geldof and others, thinking up new ways to finance foreign aid.

By autumn 2007 the review was complete and he was anticipating a natural end to his political days. ‘It was the last day of party conference, and I was sat outside a café in the rain with [shadow housing minister] Grant Shapps, who I had known since he became an MP,’ he recalls. ‘Everyone expected an election to be called… I was thinking, I’ll probably leave politics and take up publishing.’

But the election never came, and Mr Johnson’s shot at the mayoralty was suddenly the biggest game in town. Mr Blakeway was parachuted in to help draft campaign manifestoes.

In at the deep end

With the election win came Mr Blakeway’s first chance at practical politics. He was brought into City Hall in a temporary ‘transition team’ given 100 days to kick-start the new mayoralty. When Mr Johnson asked him to stay on, the directorship Mr Blakeway wanted was housing. He was intrigued by the new powers and huge budget at the mayor’s disposal. ‘We had a real clean slate, accentuated by the market and by the fact that people were willing to look afresh at things,’ he says.

The appointment raised eyebrows in the sector. When he took the £81,000-a-year post, Mr Blakeway had no experience in housing. But he claims his greenness as a virtue, insisting people have been ‘refreshed’ by the new approach at City Hall. He describes this as a willingness to ‘show leadership in a very challenging market’, without being ‘weighed down by baggage’ built up ‘over decades of working in the sector’.

Ultimately that leadership will be judged on the success of his policies. And the mayor’s defining housing policy is the abolition of London’s 50 per cent target. The pair were so confident of accomplishing more through co-operative negotiation with boroughs, they matched Mr Livingstone’s commitment to deliver 50,000 affordable homes between 2008 and 2011. Since October, City Hall has been in closed-door negotiations to agree individual targets with the boroughs.

More than any other, this approach presents a microcosm of what a Conservative government’s housing policy might look like. In its recent housing green paper, the party promised to revoke the system of centrally imposed building targets, replacing them with ‘incentives to develop’.

So how is London’s localist experiment going? Mr Blakeway says the boroughs have so far been persuaded to agree to ‘more than 40,000’ new homes, a figure he claims is greater than Mr Livingstone could have delivered. In the current market, with few planning applications coming forward, a percentage target is not the right ‘lever’ to deliver affordable homes, he insists.

But the mayor wants negotiations concluded this spring. Can his office get the boroughs up to 50,000 by then? ‘People will be surprised how close we are to delivering an unprecedented number of affordable homes in London,’ Mr Blakeway replies.

Is that a yes or a no? ‘That’s my answer.’

The council leader

Stephen Greenhalgh, Hammersmith & Fulham Council

Stephen Greenhalgh gestures to a map of Hammersmith & Fulham he keeps hanging in his office. Four areas are marked in deep red, indicating their place among the nation’s top 10 per cent most deprived neighbourhoods. They are all, he says, areas where social housing predominates. ‘We need to challenge the needs-based system that underpins social housing,’ he says.

‘We are challenging the current orthodoxy about how social housing is allocated, because the social consequences are so bad, the economic consequences for the competitiveness of our inner cities are poor, and the financial returns are risible.’

Few people have done more to define what right wing Conservative housing policy looks like in the 21st century than Mr Greenhalgh, who has been leader of the council since 2006.

Until now, this has been manifested largely through his own borough’s policies. These include pushing for shared ownership or intermediate housing, in place of new social homes, on developments in the areas marked in red. The borough also uses what little discretion it has over social housing allocations to prioritise those willing to seek work.

To London’s Labour politicians, this approach falls somewhere between social engineering and outright gerrymandering. The council wants to drive down the proportion of social housing, opponents say, because it considers social tenants unlikely to vote Tory. The suggestion provokes scorn from Mr Greenhalgh. ‘This isn’t a political game. What we’re trying to do is achieve decent neighbourhoods. Attract a mixture of incomes in areas of concentrated deprivation. Look at the map – that’s where it is.’

Now the 41-year-old has turned his attention to national reform. Last week he launched a co-authored paper calling for radical deregulation of social housing, to empower councils to break down concentrations of poverty.

Principles for social housing reform advocates scrapping the needs-based allocation system, allowing local authorities to house ‘a higher proportion of economically active households’.

All social homes would be switched to a form of assured shorthold tenancy, modelled on the private sector. Councils and housing associations would be free to let, sell and redevelop their stock largely as they chose. And rents would rise to near-market levels, with government funds currently used to develop social housing shifted to increased housing benefit payments. Local authorities’ new freedoms would be matched by a duty to ‘fix broken neighbourhoods’.

‘If the vast majority of people are workless, or have lots of issues, it’s not a great place to get on in life,’ he continues.

‘We are arguing, as the government has argued, that it’s very important to think about mixed communities.’

But the solution he proposes would demand slaughtering social housing’s sacred cow – security of tenure. Local authorities would have a ‘duty to house’ only a small group of people deemed incapable of housing themselves, such as the severely disabled and the drug-addicted. For the majority, councils would have a duty to help them secure housing in the market. Does Mr Greenhalgh think any government could get away with this?

‘If you want my honest opinion – tenure will be the hardest battle to fight. That will be the hardest one to deal with, and is where the battle lines will be drawn over this issue.’

Does he think that this battle will happen if a Conservative government is elected into power? ‘It’s going to happen sometime, we just don’t know when.’

He argues that the time is right for the radical – and, to many, shocking – reforms he proposes. ‘I was struck by how many housing professionals are beginning to think about the shortcomings of the current system,’ he says.

‘They are not all agreed about what we should do, but their appetite for reform is palpable… The time is now to define the principles that will lead to reform of a system that no longer works.’

The cabinet member

Philippa Roe, Westminster Council

‘Not at all!’ exclaims Philippa Roe. ‘Not at all.’

In a meeting room on the 17th floor of Westminster City Hall, the councillor is energetically dismissing my suggestion she might have difficulty relating to social tenants. She is, after all, a Roe dean School alumnus, a former investment banker and a long-time resident of her ritzy Knightsbridge & Belgravia ward.

‘Everyone’s life goes through ups and downs, and my own has as well, and, you know, the older you get the more empathy you have. Of course I have immense sympathy for people and their problems… I think you’re stereotyping me.’

Ms Roe, 46, has only been in charge of the Westminster housing portfolio as long as Boris Johnson has been in charge at City Hall. She was elected in 2006 and awarded her cabinet post last May. But she is in no doubt that the major change Mr Johnson’s election has brought is the abolition of the 50 per cent target.

‘The biggest difference is his emphasis, not on delivering section 106s and the percentage of [affordable] houses on a development, but on targets for each authority, which gives us much more freedom in where we put them, and how we structure them,’ she says. Westminster is still negotiating its target.

It is an emphasis she hopes to see mirrored in the policies of a future Conservative government. Asked what voters might expect from such a government, on the basis of Mr Johnson’s example, she says: ‘I would like to think it is devolving more decision-making down to local councils in terms of what is right about social housing in their area, and allowing them to finance it themselves.’

Although new to her post, Ms Roe has a pedigree in Tory politics. The daughter of former Conservative MP Dame Marion Roe, she served on the high-level panel of private sector experts brought in by the last Tory government to set up the private finance initiative.

Now she is looking for ways to cement what she sees as the ‘core’ principle of PFI – that the rigours of a competitive market can drive up standards in the public sector – in the relationship Westminster has with its arm’s-length management organisation, Citywest Homes.

Last autumn, relations between the council and the ALMO’s senior management broke down. The chief executive and the finance director both resigned. Chair Kevin Bond was sacked a few weeks later, and he accused Westminster of trampling Citywest’s independence.

Ms Roe believes the ‘root of the problem’ is the way ALMO contracts are structured.

‘I think they were set up with a naive view that ALMOs were going to offer the best of both worlds, where you would still have local authority involvement, but you would have the incentivisation of the private sector.

‘In fact, it’s the worst of both worlds, because they have independence… but from the client perspective it is extremely difficult to terminate the relationship with them.’ This means, she says, councils do not have the ‘normal levers’ a customer has to push up service quality. As a result they become ‘too involved’ in managing their ALMOs’ if they perceive problems.

In response, she wants an arrangement that will make Citywest ‘more like a private sector provider of housing management services’. This would involve regular, possibly annual, opportunities to review the contract, and the ability to terminate and pass it to a housing association if service fell short.

‘There has to be a genuine market there so that there’s real competition, and people are genuinely trying to give you a) the best price, and b) the best service,’ she concludes. ‘And for them all constantly to feel that they’ve got to keep on their toes, otherwise we could terminate.’

FURY: Cllr Anwar Khan accused his white Labour colleagues of halting the ambitions of Bengalis [TOWER HAMLETS]

FURY: Cllr Anwar Khan accused his white Labour colleagues of halting the ambitions of Bengalis [TOWER HAMLETS] FARCE: Labour's group leader in Tower Hamlets, Sirajul Islam, was mocked as Danny de Vito lookalike [TOWER HAMLETS]

FARCE: Labour's group leader in Tower Hamlets, Sirajul Islam, was mocked as Danny de Vito lookalike [TOWER HAMLETS] Independent councillor Alibor Choudhury 'joked' Labour were like Oswald Mosley's Blackshirts [TOWER HAMLETS]

Independent councillor Alibor Choudhury 'joked' Labour were like Oswald Mosley's Blackshirts [TOWER HAMLETS] Veteran Labour councillor was visibly shocked by the behaviour and accusations [TOWER HAMLETS]

Veteran Labour councillor was visibly shocked by the behaviour and accusations [TOWER HAMLETS]

TV: Mayor Lutfur Rahman, right, being interviewed on Channel S by Mohammed Ferdhaus, left [YOUTUBE]

TV: Mayor Lutfur Rahman, right, being interviewed on Channel S by Mohammed Ferdhaus, left [YOUTUBE] CONTROVERSIAL: Tower Hamlets mayor Lutfur Rahman was expelled from the Labour party in 2010 [TOWER HAMLETS]

CONTROVERSIAL: Tower Hamlets mayor Lutfur Rahman was expelled from the Labour party in 2010 [TOWER HAMLETS] CONVICT: Mohammed Ferdhaus was alos jailed for insurance fraud in 2008 [CENTRAL]

CONVICT: Mohammed Ferdhaus was alos jailed for insurance fraud in 2008 [CENTRAL]

![KHOODEELAAR! Documenting Tower Hamlets Council; to make the Council accountable and democratic [3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhLq4Y8PMJoFDUHqnf7Phfwb7TOe_VQdLXp8z9Dd9K57-srq8r45lE7uO6JUS5Vy3-wjFDqDN1LozeIq1y8UNACVS-EvCKN4E6QEs850abejXxCZfrRFVBABeAqX5KteEcDGxHW6hop4EI/s692/AADHIKARMedia%25C2%25A9MuhammadHaque+pictured+TowerHamlets+Council22May2013.jpg)

![Tower Hamlets Councillors are doing NOTHING to stop Govt attacks...[2].](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgHEO4JyQZWCGfUHdAszhmJhYI6DEoW5j7fXjXx3Q1qxgqdLl3P7TMnvfQEy4qgVLm_X5pDuuqmRU4b_RGjukyfrLjoSYQXSvMN9ja-Sf-kyohXNl2mcV1omTqGGBS0XkVlXDvGslzKFao/s150/AADHIKAROnline%25C2%25A9MuhammadHaque+KHOODEELAAR11May2013.jpg)

![SAVAR Casualties number rises, as EU "acts" on Bangladesh State failures [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjGnAx6RlA2Iq5u3fFSiPMNKFnLO767C3MDBGAR6CpLBotJnEo-43rXvUTolKjoCrmVZyIDBYaPaGj3cZUFJYcsooUXHk2q66hbOoawecQM0T0lPFLGEnjWVuvIOXpNtjojPafynhoGGkI/s150/Savar+Factory+Dead-+is+London+PRIVATE+EYE+cartoon+%252522funny%252522%253F.jpg)

![Crossrail noise drove family out of their own home - into a 'shelter' in another part! [1][b]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjEElhpnoP9p35VtHPNWJOW5KtxiLqTlgYxYX9s-2yZMrRW0HmLXWT2v90JAqFx2GAUqA49p7DiHMJtn81mhuah9Nu2F0tJEIUdabtZUIyfeUqmKN67dsRQ0RCJco2NO6Hwr8-copE0SUM/s692/KHOODEELAAR%252C+from+2007+to+2013+on+the+Crossrail+nosie+attacks+on+Vallance+Road+near+Whitechapel.jpg)

![Can Lutfur Rahman stop Tower Hamlets Council sinking beyond repair? The SPECTATOR 'debates' [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgmi-hOqRbh8YdQRftgU5sKpIX_xKfJsjZtWo9pPLe1yvx7HoITJTaMPiaRAQyACsl8MLj0leT2P5ntzczH53NuHnBjXUusgQm86_rjpRk6vwFgIwO9ikYIdVlWAkkhZyXEmW3NumViH1I/s692/AADHIKAR+including+Sylvie+Pierce+pix+in+Montage.jpg)

![Can Lutfur Rahman stop Tower Hamlets Council sinking beyond repair? The SPECTATOR 'debates' [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEibeWB2xnypkedjWXTiPMXBZ31MrjTpeb1H1Ehch6MmTsyPrIGku4VcLqNuhTlX0sml7nYfW5QKZ9YzVfTODITemUZNd9WBcnFtr-pYMORCOTc9Impp4i63Ds5YbVWOLHeUapLPUXK-h90/s692/Sylvie+Pierce+treturns+to+the+scene.png)

![Bedroom tax: Diagnosing the multiple fraud by the "Social landlords" [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgoyFcSyRfcgMqrmr7GsFgK4iQ3hZnw3e8BlNJeIfbQ16v2s0ta02m-Y1csJHCBjbaiEmMUsvL5xAAKtXCxbK3cMpxkTL6gpKkqIpbn4Lg1LskAdUIGJbO7USYHpSqS4pLHi9uWy8JPpfs/s692/AADHIKAR+Diagnosing+BBC%252C+OBSERVER%252C+David+Orr+and+NHF+01+April+2013.jpg)

![DEBUNKING Myths at the expense of the East End [1000]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi0vKwGHDcfsE7_r7cIH26t9Yqgcb6sHeDosjQGQJ1CrTKPvBFK2tjg4syW9slW_CiC1CweajhXRiMi0aSLmPaUDGrLSFaQ0rkeqBkswQks0D0qYperv9noCVgEQdm9H1HYpqzrgnbTEGI/s692/Lutfur+MUST+SHOW+What+Crossrail+jobs+he+did+the+byte+on.png)

![Tower Hamlets Council's very own Housing benefits lies and nightmares [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiEkc4RPX82ZuMPiY1xj1LmW6QwpCBLjb7lIeF2BtBPuatNAdSR76dl61_vNFmpJXKnojL4wU8AJkAUiHaqdfY4sEKO9045kPEexNkiHsCLu_xFcbBOAuMmYFoXiOE0EMUDFHa0kYaxFjU/s692/Mistaken+rent+arrears+nightmare+-+Council+apologises+to+family.tiff)

![Racist resurgence in Britain given legitimacy by the Milibranding of the Bliared Bureaucracy: [1b]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjv3o6m-KYLuZKVJdjl7ZqxmJLBHV3xvWDjkHQV73z771a5-MQZYBnXXtaZXYh7dJB0Y3jybUVf2qgYOJvloPAUY_AgGkmXsRT8Z7Ww_Ut9bujEgX1Zf8vvm2qAMfhAFtMZx6vNIEbMGYs/s692/TESSA+JOWELL+exhibits+the+gritted+teeth+of+the+racist+core+at+Labour+Party+Establishment+under+Milibrand.jpg)

![Kay Jordan crucial role in defence of the UK Bangladeshi Community: The KHOODEELAAR! Campaign [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhiGOlfDCFeu1eqXknJTRE-uUUh2aJ0KoE68Dac93NAOtMPQiG0f82BETevDbB0tLPtEIc74sh_YgRbShdvdYPdQkYOrsXl6ilDH9PEtl6kugqp2pAlx6Wg0xCmaXJ7US6s_Qmg7qYI53Q/s692/Kay+Jordan+in+Muhammad+Haque+Commentary+Banglapost+page+26+Friday+28+Feb+2013.jpg)

![Say No to COUNCIL SERVICE CUTS in Tower Hamlets: Say No to unfairness in Tower Hamlets [c]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh0RCybipFc1NULfWDoB_KpyW-tp2Z06_IJWGtd49o-TSdptet24kdeB2MIV5230IHZR22BJajj7ThapFJBmwS3zwslnjfnehkRpGzb8iqAU6_8NTT4ibzTvn9bbi2oQxXoLcHlpHuiPtY/s692/MorningStarfriontpageWeds27Feb2013BRUMCllrsfacepeoples%2527wrath.jpg)

![KHOODEELAAR! continues to point the way and provide the example of how to keep Brick Lane ....[2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiUjvCmd_3MbLemcj7l0fkiQ21M12zGmlRpswkYWjWk1QLdbQ3EN-cHI4i4wWqZZlSHjnXVk4AeTbDaPt2yd9vUUYSNTa1ySswMu-Ew2LgLt-_jtyGnrMIxmoWbOIswmvAZQR6l4lJ-w-Y/s692/seelotee-1.jpg)

![KHOODEELAAR! Campaign Hour! Some key Ethical Sources for advocating for rights [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhQSi_a7FGpEKlNqVmnw4A2Vn-hWEseQgsRJuyAQ9fdCQ6L7rhXScypiSV7QvXMiCp042YVxy1G6AWhTokoLNq2lgicsnn_vPJQSxKC_BGliBrZLEP6Heif04iWAQFHTSKk65hsPBzuEL4/s691/Muhammad+Haque+presenting+KHOODEELAAR%2521+Campaign+Hour+Thursday+21+Feb+2013.jpg)

!["SAVE Altab Ali Park from hateful Bangladesh-linked political groupings" [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhtf0cUiN4Ue3gtFZvl7srUHO0-Hbuo4XDJZG-XbDqgDKKIotOEMjID4MltiHzSp8sh9uBA8jqppR1HXbH4GbF9MY23zOj7GkZ-fyys1aabBTklf1GWfxTuZVGGso6O5dKaGrXzCpm_I5A/s692/AADHIKAROnline%25C2%25A9Muhammad+Haque+Picture+of+rally+at+Altab+Ali+Park+Thursday+21+February+2013.jpg)

![Altab Ali Park Thursday 21 February 2013: very odd words! [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhW1SEGZyLDVQq7H1CuzGIfBvvLcfi_GibN2oJmQhW79EcmKcUZFIb0zjjfQIrDdB18tnmziux9haUngvM9xTI0ouG_aXZ0m5uLt8OHj4er8WX4pR10BST8BAEDHLeaD8IQunO_U4cY4qs/s692/AADHIKARONline%25C2%25A9MuhammadHaque+Report+from+AltabAliPark21Feb2013.jpg)

![TOWER HAMLETS COUNCIL bureaucracy is in a state of crisis [22]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjEQAG9Z3A8vvCyrg3ef6ZvpTXD0K21IXXZMGcdBvXQMfdh6V9Fo46xIA9HowXB9IcUl_A2f1WQQVW7w5u596NerUe4_9j4RVHSpX5TFJYTro9ffp24bRvKdclor0vmkO6NJLcH3A9vFl8/s692/Overpaid+rail+Bosses+cause+anger%25E2%2580%25A6ipaper.tiff)

![“Tower Hamlets Council in a state of bureaucratic and administrative dysfunction” “Discuss” [N'th]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhzbJQjm-P5TNBngBK69RgBnJ_2IWAzrAoc9dtZUi81FKBRc6WtQ2fz88aHdyoRh659IP-TUArmX9MiCnD-Vi4YFY4Abb3qM5WRNGrMqHiEeXLLbZmMdvHQ1nkKQsnHkGvBrA5fWtZSCkk/s692/Carole.Swords.speaking.against.Council.stock.transfer.tiff)

![Council [Kingston, London] fatally let down victim of violence!](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEib75BhaCHvhIeIb-G509DKJHEwJH0gIqCPUyZ9g61NyudUcpId-uT5vC425B71KpYdvBh0XNO1nEwPTiojCxtMbL0sZK3lzZ1IO7m85ALSdbr7iGAv0dAVw-V9oz4xS1c8HVYAnMOos78/s692/01355423900i.jpg)

![The © Muhammad Haque Lines of Sixty Long Years waiting to hear a true word: REVOLUTION [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEheW5lgh6bkGLa0goV13Ylbiy4Ehn8Fv_nkb1_sqEzoI27YMYyi-NOgnMSLcGaiD_Rd75UXYUIKZcnznc7n0GhySb9N_zxtm8sQ4W23CvJz1rQizBcItal7JZpRFgjfeo-j2V-KXpdf9X8/s692/minar-e-pakistan-tahir-ul-qadri.jpg)

![British Media treatment of "Milo" "the magnetic cat" [!] shows disrespect for animals in Britain](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiJ2WgWNN6CwU3FqSkjZ57nSqifq0hhBAfeDZJYqCdqub4oH1Wmj1fY_BZTAsCk4Sk60kEHTAEEkUq4s8fyY1UXGtMvx0XjLqjSscAGctrJ1npfoVxjPzetEehYZGYcqiG2uUZMBdSo6pg/s692/Andrew+Pierce+is+mad+about+cats.skynews.jpg.jpg)

![Muhammad Haque Diagnosing Tower Hamlets Council that is UNFIT FOR PURPOSE [12]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjrybCUOopW7i0-1aNKU1WKtJQmIqaaGUIzmTNZnv72b1hxtWey38eAfwL1xOKg0u0vCLXbj7unMzlhdTesr6CQDpS-Uhly8k4ELZWUnWGqU7NL0XXRdmwhHvRLJ3xkRpBd2XZvuTSzoOc/s692/Khoodeelaar%2521+try+this+logo.png)

![HOW TOWER HAMLETS COUNCIL has been made UNFIT FOR PURPOSE [9]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhzKor0ZJeWK9xyOUX9ooTq_i1Wt7fOYF3u5HJd7K9yNs4X8iLOjqwKNwOzYEIcW1CW2XJbUghlsu1BzAWda3-EtgcRV1CNpBBAl2wB8Ws2YEypZzj6Y8SrGNL7tqKib5MO-NegxqWxxCM/s692/AADHIKAROnline+%255B9%255D+diagnosing+the+Tower+Hamlets+Council%2527s+UNFITNESS+of+purpose+Thursday10January2013.tiff)

![TOWER HAMLETS COUNCIL Is made UNFIT FOR PURPOSE by corrupt, racist emplyees in key posts [8]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjNDj41AJV5LzyZeJ65aivju5IQz-YkUvI9A36ul-t_fLz6HoDa4OCpBssTRGzfeNoS1Iih7fI2ObmikHGhbUTrrYFFsPvwChmAF5_2EFXuFZo1Ep6qSveH-M9jOB8ZJja1Mt_lxs2JDrU/s692/AADHIKAROnlireporting+MorningStarFrontPageWeds09Jan2013.jpg)

![Tower Hamlets Council is almost UNFIT for purpose[ 6].](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEihYSnuSr4-uk1-CMDUwxZToDFvmiTeO8g-yu_zT-r3rlrW9dlKPC4dbY9OcODzNbsF80NmxiTjJKL8REyelA5wCPrHNss3uEvmpOMOOQcXTSMkhE6Wlr-13bf-Dn0fWqxjL7Emx4EpT5g/s692/KHEYDAIEELAAR%2521+NeoCons+shall+not+pass.png)

![The © Muhammad Haque Daily Ethical Commentary [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiy-091neF97ovrZ7hyExbtgnPeO74kMt7YTOIfRTUpzEneVXICrh0ebxwF4th0HBHD0qx5c0Is3UiZ4XiMAiWz3YaS9kj8ydtrQqaSuLv9C2icyU1qcn6H_po44HGZQ6K-NNOSpT1lCLU/s692/The+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+Daily+Ethics.MORNINGSTAR907January2013.jpg)

![Who dared violate my child? Lines of Questions by Muhammad Haque at the Rapists [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjc6Kcv_nlzvMCTBTlsVBt008Hk9pNRMmS99leUd5CRuh6lOjHwK-jg0HXBRurNzKQsbPsrqniWDHzVh-XJh_5sPyuMdVchBNKoiUl-16KRS8jc3tCuCiTvsuBFtGaMMCrQljY281Bn4sw/s692/rape+map+of+India+wallstreetjournal.jpg)

![Examining Tower Hamlets Council's POVERTY-CREATION programme: [2] : Whose idea was it to 'TELCO'?](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgJVGsIYGnOdKdbA790JB-2ClrD2WbSOmNCZ5JefM3Hz5i-pzapme0Jwe8HRH0Gk9nppXIjU8yNJ2anqkEuau7fchttdQTlTMyjXm4OeUfsYksZ8gdw5_BrLEAlmZxFQ2bO5IuyZoVw3oc/s692/3.jpg)

![INVESTIGATING Tower Hamlets Council's Policy FOR KEEPING POVERTY IN [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjDu920WoFwNZkZWk8g9bDhokICzc2VB0tTE66scW6ZhyphenhyphenZMVxO_dzDqVFiZzk-nqyUf5QfKyHqYawUJM2VQQ21e8Hu73VzYC-l7Paxx-R1aRr28Z2BFn4TfXE2xBfnYRBgx_l6ompRVy5I/s692/_Muhammad_Haque_picture_of_Lutfur_at_164_Brick_Lane.png)

![The © Muhammad Haque Annual Political Poetry: Christmas Day 2012 [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi4rsN3n6MqPq3NDD6YpfJd2HDdkfq3ZtEsqchJnv1OCDkPlx8D-ldT6nC9p5MxbbeMcCgKTwtEBr3RxxzgUhJXpevhfmjmv8eYkWWI16tWrVSY-BDSYgQGrxMrNxKJ9RawMriPeR6aF5g/s692/LONELYUK%252CDailyMailfrontpage2Nov2012..jpg)

![How a London Council leader [not in post then] lied against Muhammad Haque & backed City of London](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgqFyhy-EvNHIZU45fiJXtKPLDDSct6lVnUABcmIfURlyz7Mq2GMD-oicAeg-p_MnnWTN58Mbld1FLtMCM_G3he19t-wjVqmHGUGgNcTybtSdse2MhW2xo8abtxsnhDOZs3k3SFzUKLsUY/s692/Kheydaieelaar.tiff)

![CRUELTY of the Courts, Cruelty by the Health system and Cruelty by the careerists in PR, Media [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiMTDedD-BLhAv8I_n5NEkj7hHillKwaeW-LRBkpVIi0p3KOUXP2YTmGxD3zK_Ka5oAcoxX2hrsPnV97e2JUO384a2YjsjRWsMcUQJDRaJ2bh_TiNtKjlMBNEKNneRVqy7pDWRdKfullgg/s692/Sally%252BRoberts%252Barriving%252Bat%252Bthe%252BHigh%252BCourt.jpeg)

![Hopelessness of homelessness caused by bankrupt politicos of Britain [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgEgXham58apcsRoABri19bvrKW2Wrt-0rW5AWFwoL_AQqBnDHRvcecxTnHZPSQJt1vb9b5Mui3tXBEzmAwkEuwPakKbrrjVbflUqEq4RDGjnYBhGzpL6qQJ0rEOwTG4gVmxhT9ELmBqe8/s692/AADHIKARonine+diagnosing+the+moral%252C+political+and+democratic+bankruptcy++of+the+UK+Politicos+19+Dec+2012.jpg)

![All children, babies DESERVE protection from ALL attacks! By USA gunmen and by USA military... [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiQBs3mAyUsNiodvG91Ycs9_AJl3Kovt_YMyGQciiCKAub4TXlvVAKTyj6QpJ6qP0URCCuQfXSBqOce20vA0hkcJBvTuoYchQC-SMtjWLbKRph4Qh6lTB3GUgBjWBNAl2oIfAvvlts9l1I/s692/li-helicopter-rtxsz7r.jpg)

![KHEYDAIEELAAR! UPDATE: Muhammad Haque Political Poetry “in English” at Ed Milibrat! [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj4BKNKoKfVvRpBPcvIIBobVdelCypAbeWIrZk0sfCwjzSir4SNYMhNhb5njrMn-wsvuuCKWujzShG35vpcjlX-QkgjCspZaRZpiyK_qNMjNDes9Un2ZFlKEuiS1uOPZPd-Fd7HUnVVZtk/s692/KHEYDAIEELAAR%2521+Update+on+KEEP+%2527Banglatown%2527+IN.tiff)

![Racists take sense out of the Census! [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhbAE2CIufD2B-lWHxIvsAIX9soqVxl4oQ4JmgFRTY4apBndPEIxe21Wb3LgOQ9RGrU2izJYr47bAWIk7qOZIZ7ux8jM6prNj_kRNVxjZSTroh3b5VzrKFXwnGZAi-vQu7juUo3D6M_vjo/s692/%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+Daily+Ethical.png)

![UK Govt is forced to concede need for massive review of the key Policing values [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjoWm7BDSBNqDOmsm4c_QDHAQKrCsP-pHEW3BueV-fxsZMyqy09vlPh1EAEBa6BFymGUR8TU1XtZMkZ2gmm73JIMEOrgprzo9BsbC0m7Sy-gZBqSR056VA3caZ1z-8-runJh9VSaE8csAk/s692/Hillsboro+injustice+late+admission.jpg)

![The 1970s battle of Brick Lane Lon don E1 repeated now in Greece by besieged Bangladeshis [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgy8tfOYPQ11n3Wujzjde8gWxWfQgOLrb7eWW79vyIoLclJl5vi9SsUtAcG8q7eIr6qY3dgtGWpM4VhNVZ2XlDJFWHraZyYBwtLBDRCebBWCmi3iKene6X-L8XDjn7XoAeqxmkaVOum2YU/s692/Kheydaieelaar%2521+Bangladeshis+are+under+siege+from+racists+in+Greece.tiff)

!["Bengali" "Seelotee" Channel BANS callers from speaking Bangla or Seelotee! "Gourober Beejoy" ! [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgNwnKVk_JAGcKXkYHB0xt4_ZxySQExXlH_e1r4k-4tBWEqmVTgwL3aFZEOLsJ1RH5T2mXo8a-bL_1O0t0ouqhXiA88JEam-LbiL4_DertJ2g9jQUfYm_oyex-CTm_qF9qLXy7X441ga8k/s692/Masroor+bans+Bengali+on+Channel+S.tiff)

![Guido focuses on Guardian's guardian Polly T [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhMJdIjg-fAFucprjIWAcpv-y9zU2bqDmgWOthLldZHQBGHVij7sQo-SPrW3R-ZDO7KnSjnLbKEuCdTk66qNQot29lTadcg1vvfO-ekP6TX_pvQRlEowfdN5hwzzGZ3pqcZX1qVpgJOVrU/s692/Guido+focuses+on+Guardian%2527s+guardian+Polly+T+%255B1%255D.png)

![LEVESON in Brick Lane! Continuing the arguments over "Banglatown" name [11]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgi2spJ0L3031tu4j9TWqz6KBC_LcxqHUV7Iep6w4lweRyYae8EcJJjwrKdKlXWzUUjSTIrPbvYFYRY-PinClAskHKg4loieP7CqdEUMJqUCAx0l_TfbKseV0m71ySv34AXwa_botoEo_Y/s692/AADHIKAROnline+diagnosing+the+British+media+1015GMTTuews04Dec2012.tiff)

![Contexting the battle for the East End: 50 years of struggle to stop Big Business taking over [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEirfNai_H6iqoJgqMnZqkn1St2ixIRlcTdpx3zfNjixm2eIRj_k0xOfvLKVTsdSmkPOkRJijPxTeLoElJlyC0Ln8a-I2EBT0pusSRpOX5mr15F9756QCtYRtzcbt5qIL0k-3BK0VIXRLpc/s692/stadium-and-park_2195856b.jpg)

![Tower Hamlets Council democracy and service deficit: but who will bring to life the Opposition? [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjFxIXbnA-WHork0fyvjIXQWn8z8lzc8Hq9JddLOjLPmhKEPiBxZCj3X-7Zqj5EAteqowVWKLVdyDBzJxX1JrugSfzSKEcDOVIkGcLIdcz_4VAHakbdfR_k5lZooYZUxzmaeberFD24aaU/s150/AADHIKARonline+reporting+on+the+campaign+for+a+%2527NO%2527+vote+on+the+mayor+referendum.+Picture+used+is+from+Channel+S+satellute+propgramme+item+of+6+February+2010.jpg)

![Who is fomenting "faiths”-linked hatred and intolerance in Tower Hamlets-[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhnmVlvUxMKLTR1rVM5rWrG0BRVOojfCRHOIdwAcRvbxcH2CWblGttX_YafbaB4frMl-z2Z89F49ci7d8hMB6JIjDQPXWUrecm4-Rit69btRrZGW4lk5rZsjiAtQw_BJFBi_qtbZZl8cwk/s692/EDL+No+More+Mosques-1.jpg)

![Clueless Councillors and MPs utter banalities over rising jobless numbers in Tower Hamlets [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiMw0ISajOsHUYUcY_72AGayxMHldXHkevPuprIv_GRpgGdV73kzUaao21Y37YQOscm7Zw7V4LdTVW32xmsg8BL9M9oP9llBbDHhYD2692qbvQ5GFt0BDfaYHhcWvhPtGD6P_hSKWRBVBM/s692/A+Flickr+pix+of+Tower+Hamlets+Council+Tory+Peter+Golds.tiff)

![KHOODEELAAR! TOLD YOU before ALL of Fleet Street: that the BBC was CORRUPT, incompetent..[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiMjg7AHNBw5gSzamXAt25Qo9h7GEF2rO_RDfWaN_2ge-j6wJfuOjhhKiVHLwzsomlYjYvmXf7wJeFwUagHVBYIsl2d4Q0YLz-bXCr_TOq6tM3_lESsIbuJdW680j7VPkBYyQLQIAddbjg/s692/AADHIKARMedia.Diagnosing+the+Sunday+Fleet+Street%252BUK+Frontpages11Nov2012.jpg)

![KHOODEELAAR! Manifesto 2012 [4]. Tower Hamlets Council MUST STOP using lying and propaganda ...](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi06dgEuG5EuegWJaRpHkGR4qiYSRUURV-y_Ma-N4UoVU3zMcUM5xBEjEVDw8oeaAGn8TJhTzVGJ-h_RVsG88LFvl34o0eValuOrupNh5fdeNHydEzoQQwSBYKWRYOM6XMhVNygspmWq4qT/s692/Lutfur+Rahman+with+TH+Council+of+Mosques.tiff)

![Exposing and rejecting the lies of the House of "Lords" [!!!!] Crossrail hole Bill Stooged Committe](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhD4PMMl4Rl8IxB7OxpuXpJRep7Qqxj2J5rPb0K4PiZpMwFRcdRLG2gd-B6dOectAM8XOKhn2b69YyCtwoOsj9tRBmiJ3wGqRX35IlX3e-2LiMEHa1X8vGhTa6viC8NZoCehlDO504zk0g5/s692/Muhammad+Haque+for+KHOODEELAAR%2521+paid+HL+petition+fee+30JA2008.tiff)

![DRESSAGE is outrageous cruelty to horses [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEifRosJndpM9n43G6Rr_O2XtqhL-jEz7GCwevtbXRq95InQhvwdWXtKlA1zU53ijaej1zs_4kU9NfreyXdwf3qjthDkHWRebeJ5ZUHDjLnhtTXBZN6HQ1iOUsm2Xgsw_nXtvdC1nEUN43XL/s692/dressage-1200-1.jpg)

![© The Muhammad Haque Political Poetry Against the Lies of Big Biz-gripped 2012 [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjp_j0F71HKIBxpjAcK1SPkUWScmxV9T4KhmiLXqz7KxbuSJtJjB2xp62GEhMPaG92YzjbcEe28DkyMEko6dxjTj0SHgJLwOqQHToW2csjfC6yMQ7LeckGbabrOFE0N02wVNIIL2Y5-jD77/s692/Image+used+with+the+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+Political+Poetry.png)

![Muhammad Haque tells EVENING STANDARD to tell the truth [1000th]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg1N1wwaE23IY6wcB1F1vGl93bvD3CxeBzfMDoQhh0NIW3hL5V-XcF7L75XJ-SXbagN0_ZcqWT53LZtA__jgJhCUS4rxJIo5DYI6ydtqGtejXA_YLsDCxqG-vC93jlY_cdzsJuqUj2F4owB/s692/es+frot.png)

![adhikaronline Original diagnosis of the mainstream MEDIA: G Galloway [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjSX2Ka25wQjtSSYn400qJfA6BvgGcSixgoSYHCB0oO0sRm4QFbWcuweK9wFurYGavvEtrbg_lKLiIshKCRqQngLyGwOeiJFZaIWKPXst4vJgIFKe-SgI2P3vslgGINBcztD3Yblv74-2Ad/s692/DailyMailfakesaid27April2012.png)

![Evening Standard piece about RICH BORIS censured [retrieved] 1434 GMT 16 April 2012](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi9_Kc5cUxs-KxP90v4IAeRZHSJ85ayTBJQz7z-StoPRTM0rOY1OjIQGTOK0dqLOIDBijU3UonI_t8_DOZxhO3Io7gzrWrsWwOgc0hkEgsLXQNhUVY7KcbKXxgJ7qhMgcsSZH75mpmvOYbh/s692/Evening+Standard+piece+censured+%255Bretrieved%255D+1434+GMT+16+April++2012.png)

![London Mayor poll: EVENING STANDARD suppresses real comment on ITS coverage [4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjfSImGqBl78j3wiWXEjXeVX0OXzjgQQms27bPEPF3ulleGFWNcDYdgIZZkF9bocppzIxq84M12yzGdqhrstO4V7GA2Tc8_KYRNKpvqZxO_IyEGNvImpc1G7BD80ya0Yarjcr-uei6votSk/s692/header_logo_new.png.jpeg)

![Tower Hamlets Vote fraud scandal: Time to practise the lessons of the Poplar Councillors [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh6D0oHAQAc7b0cVxd1751jo4gpV4qy6TV3gITelpMcf6FvD91AgpC4-e93muNkaG4b6KHNzf-jtj_4MIAUPBySdEwH_oRQNO42nfylHD8JSdQmTXRbmJZcjeGviD4yFlSkQJXYIhPwlVEU/s692/16183022.jpg)

![DAISY SAMPSON [McAndrew] sums up Britain’s “gang culture” politics as seen in the row over Raisa!](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiDP8IXhiH-86RKoDnMH0bDWPHSnBPp-gxnV-OK92MqqGtQzMBJsN5xoyvchsf8bstGqtb-B2U1skUybHkoQDdZxrfyywmYtzrY912z0uyJt77MPiEXEdRuVbDYbGQUN6eDT1_0RqMwTlmC/s692/AADHIKAROnlinbe+dianbsoing+the+nedia+on+UK+Poswer+Gangs06March2012.png)

![Tony Winterbottom’s contract confession further undermines the claims by Tower Hamlets Council [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgNv70McmZcfGoMlxBTqDnY3eegHIzyh7V3HUQfVzwqNGWLgnL8tddRauU1JWaH0RLneUmXshIaHGg75mlhkxqHpt9df-loYYAQ20u8F0kq7JnzG8LUKHsPtCOpJfMYHiJw8_Tl9epGKiRT/s692/Daily_Mirror_17_2_2012.tiff.jpg)

![Muhammad Haque rebutting latest anti-Ken Livingstone propaganda via the EVENING STANDARD [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi3oR0QPmX070Ttm91cpR6yThXF051H4C0G4iZHqlTldkUWfVc1FooP-hZjcBkDjn2_CSR94JnOMCdJCXG-gNQa__J8cVkMQJu00ZnLttItk9cKRJmhkPxYY7Jw2FZIUHKP-7V3MSlGJK7q/s692/ES+website++picture+Ken-LivingstoneLutfur-415.jpg)

![The poverty of the "Labour" Opposition in Parliament is KEEPING poverty rising in Society [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjAxeBUFgmJV-GfLnGZYuUPdvx4AmN9iZo7InKQccLG9881guke9Xv3S1XzhIfD7CIdCYVZFUOJy0Nvl8AHKXi_DH-XTDAWYfUs9KeHDmBys5LxIpLstM4dUSVeTVVjLdUC95ftTsKNxS04/s692/16148891.jpg)

![UK satellite TV Channel [SKY 844] tributes to KHOODEELAAR! defence of the community](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgHZVSiwqY4ij0DIJbpEdVlk1JNR1LzAenw5gPkQzOjFXSVdm3sXyVzR3PJMnnGQr6MIsefswyFaxOhShFwBFhZdsQwPIPN8haRYX11CDLXp7uUJqjjLUH5Rg842XrW7YXb3eYnpWpAElCJ/s692/%25C2%25A9MUHAMMAD%252BHAQUE%252Bpicture%252BKHOODEELAAR%2521%252B6April%252B2009%252BHanbury%252BStreet%252BLondon%252BE1.jpg)

![AADHIKAROnline KJI previous edition [various dates in] May to 24 June 2011](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlGCCTw2GbW2WyBgiTwZe5wxhGOk0NC-LP2unHUWj1STzItI0_F6vKz2dHq2dLobepBqiR7lzTcDXybIxPbefNvjwInZQeiInZH5foHD47jiGCCwGalvA6vZubpKKChY3zMz7bY_5eiI5V/s692/KayINDEXPage15May2011REAL.png)

![AADHIKAROnline KJI previous edition [various dates in] May to 24 June 2011](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh_oOtz5cmKGCg09sK4vB7BLAIRNgvBujEXctOwENOGoPcQRv9dahg-63SK8oMCXsGAU17Oy9S2vyuo1M58iyr7OWVvQJ-RpdenLdZKZCim-GleyWx73wGUm4Z5WwHm0xpTmssUuaKhF9Ff/s692/KayINDEXPage15May2011REAL.png)

![Muhammad Haque contextually updating on the abysmally poor standard of UK Parliament [3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgLedOA3ev3AxJI-hMLeW6_m6oMldoK_JsHDj-3fdcqOYD2dwJj_PdeV19PxTe9Du0_am620bMSUU6whFP5mxTVc9JiwrdsAl7FDrzpSqGUTE2S2lu_qGI28p5aG-cQoILClxWT842IqlgY/s692/Commuters+at+Tube+station.jpeg)

![Ken Clarke is not the only one unfit for purpose. His predecessor, Jack Straw too is [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgXXho20gxIUf69KJKgEWY2lX2JW8UTdYvcJOq-WSkzz4fjZ6s9Y2P_JYLcD1ohyphenhyphenCWi_GLKLR2Q8jkhNjOl2-tS_fH6n8TUl8KMYdhyphenhyphen5B6Yd9Mksx8YGTsv_8NbYY7rn4dXiwL1PLVIIhQg/s692/15995739.jpeg)

![CLICK on image © Muhammad Haque London Commentary 19 May 2011 [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg46T0ZL_JBWU-mYv-8kqjKkGFYOSVQOcg6aMmFiDlIbY1BJQo20CqHfnnM40R5sf52GxnEQPO4DoigHiJcREYFyKYt4dmJRgiNh7m9jTbEqqzgGH_uPUH7xYPXT2WlKRDRtb9YftG2knt-/s692/15994862.jpeg)

![© Muhammad Haque Political Poetry : In solidarity with universal freedom struggles everywhere: [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjMdPrUN_mxBOswmlwn_htMlRGApsvn7Yug0s029m8sAQqBUdybOmac-HVajXEEjnwiKm_uBxYl9Id9JLuGXHEYVSrwR0NLv60AK-N_UYSoXRlI04pF-F7Xq6Mtvi7xEFgnnwwm5MA-oGPy/s692/15994836.jpeg)

![Don't get Mary P started! She's hardly started peddling Big Biz TESCO! [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgqVbGyLmAPTqMtDXXVYKppdoqhyLrlDfziNtItC1_D1VPS0TlnQjDNDPrevJGHcMlg1VqxFSiOcNVO_bY2mX7UIMojko8mshmflN702s9A9Sbp0qyCBo8vuv84fQajKHZFZ7dy3rUwrANl/s692/Don%2527t+get+Mary+P+started%2521+She%2527s+hardly+started+peddling+Big+Biz+TESCO%2521+%255B1%255D.jpg)

![Do they remember how many perished of hunger, starvation and famine in Ireland? [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgmE9sQgZT6GR6vB7UlMauuIE49b5UiIBhBu4ccBuL3S8cE3mPq_DgovP8oV2F4AqnBxHRLpFQIGkHgb7s-fART9zRNUxdOZqi4TAz1LlDRrcWyqoVoScctZFzMVVQS99oEp6VhvIfokQiv/s692/%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+Irish+Commentary.png)

![Jon Cruddus [MP] on George Lansbury's values: resist and fight dispossession...](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjzNLxv4QzOsYKq8rwdjmXOJcV9PqfciK4vW7S5o0gXkxr7jwLm0fhWNiMGTH05drSBygLCqfbPvEWugMCWA80W-Q0_LVq-WH4Q16VtJTXTII7FodGciWkVOmAMX8IB59XWR6aJzsYxV6G7/s692/Jon+Cruddus+tells+Muhammad+Haque+about+the+values+of+George+Lansbury-+resist+peoples+dispossession....+.jpg)

![Westminster City Council's Ms Roe has got to do much better than stage an accessible fakery [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgP2W9hzWw9ptOJ-dCH9BM7Y50uylKVuseR4_1tZOKVG2usR02GumllJbm5aBsY3PFLWPIXURX94PbO0wvcsgCGzf72VeSSQVyeuis7Lk3B-qvofWIuC3ItP3XqytBjktAjh_0NOGh-gd7N/s692/%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+re-editing+bbc+fnl.a.jpg)

![The Power of the Old! The Lansbury's race way ahead of todays 'young' 'leaders' [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjmyt-5QFNQIk5gpZdNAAwKHa17n_mSAPjQjyGkjs83Fb0FCK__KbnaM10cBrqQTNxLeBotdet5lunM70SOoWsl6Pd4nrZchSysp8WkG02_Td_DG9OQFqpUwDLL7KLSF8PNPJbkcJscRxif/s692/%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+montage+%2526+the+pictures+of+Angela+Lansbury+and+the+plaque+she++unveild+in+memory+of+her+grandfather+George+Lansbury%252C+Bow+Church+memorial+event++%255B1400+GMT%255D+%252C+Bow+Road%252C+London+E3.++Saturday+07+May+2011.png)

!["Sylhet Channel" to "Channel S"! What should OFCOM do with the contents ? [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg6Edk13VtWSoujg97EUv2LK7weBWIzGAyvaMEQ9ibwxFg0TLyYS1kjiM0jOuaqdRn6t2iCSn-Ybyskxx7WGBhSHtZl2V6dclg1HMGQRBuyogC0jv3HuH3UUTUr1Yp8VX3FEW2CZRb3KeaP/s692/Sky814+Channel+contents+reportedly+from+Seelot.png)

![BBC's concealment of the truth costing the world incalculable amounts in every respect [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjVXG_ctAXgfCnSfhS0nFy6egPacvSV9Zk9b2W9tNsSc1DLuQs9qc4fiq7oDQxv0_wUpMzKsKu7w2dy1Sdo1xdoUaoTkdRoClh_6-ClJQgHmwLSR17ixTRvEJLVLgvsop1Xes8EfUbrZZKf/s692/AADHIKAROnline+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+London+Commentary+0610+%255B0540%255D+%255B0530%255D+GMT+Friday+29+April+2011.+.png)

![Ed Miliband nose the answer to the latest CONDEM internecine lies indulgence [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEisLtt8EUwT3cZA_PxQvIgQCjz_y8rLbdQ-u150baGx8rt57LLOb5L7Ila9dzkchPDW-h1WGb_LbXAA-9KbMEhbNQVMnqtKjUJJ-hybNNoi8i4y0v1xuFRgcbG1_6hyABEAC0pOsqtou8eE/s692/%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+on+Ed+Miliband%2527s+nose+limits2150GMT23Apr2011.jpg)

![BRISTOL! [2] Another contextual update due from Muhammad Haque about Ken Livingstone's "career"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgr3874nwgUUVh8eP5f2UzVuONAGV55VGq6CpNLN0VVoo79grtC8o0suTet08esCdlcfOpsZBSXjUsVuWfHpgMSgXdXFbxv3ye49ItiWWGi9ZTzSnkkbWB22R1E60nuLBCGIxkW5CcYFlEb/s692/15977683.jpeg)

![Kay Jordan has personally shown human care for the community under CONDEM attacks [3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgNtrJ2e5LfU72Qj6YGb-xj-72_7ElYUf9p6GsjLXiRdhItmOqsKu0luOUCGluWkq9s0rOCucEUc_hk69aXSqad5p5KHuxenbfRWdDKXh2XmSd6q7jjPWMjyIhXH2zOOxNADZQ1GFPexdh9/s692/AADHIKAROnline+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+London+Report.+Harun+Miah+thanks+Kay+Jordan+the+wonderful+human+being.jpg)

![MURDOCH and his News of the World, based in the East End, have lied and been in denial [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgqYAB5gu9N33Qi2bgmNmuHG4YAJD0HxZAvcRwNQzWIZoFWfjtvsNZOH4LaTekAmKxlUKfAdTS5nSwLN7rKu-iZyS_BoIm4hf8gw68HcomqmHcpQV4BKMjFdhD1c-e9b3f_nHNr8KwMLQNB/s692/GUARDIAN+front+page+Saturday16April2011+carried+by+AADHIKARonline.jpg)

![Somebody should stop CONDEM Dave from exposing his naiveté like this any more [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgb9oVmPb8lmxYHIKes5odbfDInZNhssaQU3Z4UrUr1QD7rGnqSMIl-U81PwjRMMHFTQ9W5O0tnlO9eQqzW_g0tJSPQIIrcLQOThWEP8qFDIFX3QKITeoVgZ9VmLZ1ncAs5uukWlITKCFFA/s692/Dave%2527s+nicking+off+the+Nicks15April2011+AADHIKARMedia.png)

![Daves lethal game of nicking off the two Nicks! [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj03VPW-TZ-R9aXTwXnBnAbre1kaVa-xdHRomRFnvhz3g4E_xpAahSu1oE0i-eHymnHnKbLR87w0Ur2UTSeu5LBSH8Y6OWVZb9OiSeKqdXh4vuJ_WKVOZ-fWXLeYOwVpU33e0JzwmIQ70o1/s692/Dave%2527s+nicking+off+the+Nicks15April2011+AADHIKARMedia.png)

![CAMERON is racing on a risky roller coaster as he revives the NASTY PARTY in Britain [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEij9CyNDqHd16XNZyjLMXpx90xNTnNxhbjL-608BZ86wPVlpQY50Ccn0fhNXhhhCU7jG7A7vj5slS-Aphqo6RzaFWXv0B-u2NsaFVFx2ylbREpo1BGFJTVaJOis2C8aduk14BcDqvT0KoAC/s692/15972028-1.jpeg)

![CAMERON is very dangerously coming apart! [3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjz68pT-SGiwoYBngpp-rNN6PZ36eykGLQmrHyKbwNBMCcyU8dlIyoVeJMuFSeNliz-V3_-EQhfmbl-PEh60K76wMQTH1ybM6kmFFb4mkjk0vLQbvvvictpi1yEn73wOmHA8PhcDB8BHWUQ/s692/CAMERON+war+on+ECHR.png)

![EAST END OF LONDON updating Silvio Berlusconi in updating George Orwell: [5]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi80ARt1nHZ02g1xrpTHS1YSQjW9B6UCMjHXwAN2mkcYtwCxQLe548QTFbP5za_P4vps1bFhyphenhyphensh7VO7sVsvj_-A3e_M-iw5gZuSYknPx4J59bX6NNWT7Jc_SZzGyK17kE8ABSDXTnlHFZoO/s692/HOW+TOWER+HAMLETS+is+funded+to+avoid+starvation+but+makes+people+starve+-1.jpeg)

![UPDATING George Orwell from the East End of London [3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgGpCWpbPpRKwOqZ8snybwoT7f7UN84nu1fnlC9SyhMDmdtW85QzeDeOottucaSaXOU0H90iRt3PY1XJkwcxBDvPwicif1Mci6alQ8BxlSaR7UHgMSR-sQVLRumf58JgeJInub0Q4rzXDaw/s692/AADHIKAROnline+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+London+Commentary+looking+NEXT+at+Rupert+Murdoch+affront+to+basic+common+decency+10+April+2011.jpg)

![Muhammad Haque in the East End of London UPDATING George Orwell [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEidCFUG1GS0DpVNGVTmILfw1jc1PbiIqCcKVcK-AkqsnRzjTWMg6QYQTQg0_QnmfepNgTrgHydTG_pr4uFiqMCP8ln8aSSG9sOwwYa-8dDeebLk7VpATy-6Pf3DmbWPFlCIc7M9IE8Jz1l7/s692/AADHIKAROnline+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+London+Commentary+focussing+on+poverty%252C+citing+the+ethnic+surrogate+Paul+Boateng+as+evidence.jpg)

![Harriet and her meaningless forays into morality as again exposed as hypocritical [4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEijGeAb-PzX5eOlLmZaloyfFtXGtasWDeAGUDdArNhRLxkHGkXd_Wvk3cF4hjG3S8GGwewuWxMSdmA7d13IoK3YPw-qBuxd1tathi10Z-KoMo8tYaT7W3iXunSx6cOIeVHHElBWdz5bDC-c/s692/Mail+on+Sunday+bats+for+CONDEM+Clegg+and+hits+back+at+Harriet+the+Ultimate+Opportunist+Careerist+Hypocrite+%255B3%255D.jpg)

![The GUARDIAN has to explain ITS role as a peddler of MIC, Big Biz agenda lies on Society [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi44-hEKmWlYisNKltv5fEiUvhujTvD7A1mCZpEHGAYSqL8IESSkuPWWXjRYKx5XF4mpycaKALJAeXm0G5elEBet51P3q99vPfrkrsYwjk58h0MGHZDte_Dj5NUJDZYvRXtKPcAilh22Icf/s692/15969097.jpeg)

![Kelvin Mackenzie is one of the latest bourgeois critics of CONDEM Cameron [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg6GxcctYbiKEyRzkvFBG9H2gXSUMo3nQgZWKFN-LaLx66HPXqrvqRaoquIdPlTZrQiB-xVajo0A2SfqezGpvRnsiy-zWErz9aJvGfasGRMFqeo0GBptlxEpRVKiDtLLAstuAnHEHIyL1Fd/s692/15968460.jpeg)

![UNFIT SCHOOLS! Barking at the BNP will NOT save Margartet Hodge's next career! [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjl03zC2fNLROKhuljoSnhDaTUOwHYk4Kyx6bBQbRnSgrjyuibPdKeTPVtlJfgjPR62xSpeOZNNVD-ssqHR8v4otaQjqtWRKw4ln3Ux8wjFZrL-Ll7WWD9n3rxqDiwIzw_w9SGUPJWuO0Rk/s692/15968494.jpeg)

![Justice for Ian Tomlinson and family : Updater Commentary 05 April 2011[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiYa12hQxHMCjfVN-6jYyhMF0k9WqfSijhfTCTLuYtGhpHU3Tcji6FZWSpDc-8dDfn6_EgqrHH-kqKUcUh_6Lej1o2hzhiowhQo_22QXuKFZ8xlwyu-MXwhJB0tB2s3TYbvN9CWRYNb4Onh/s692/AADHIKAROnline+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+London+Commentary+05+April+2011.png)

![CAMPAIGNING for Justice for Ian Tomlinson and family [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgW07WorkawIvKa39PK7Nv-RVBV03_kLfQIs69rFMNPTWNRSDZ2MiEGfiWoEEq-_K9o6R9P4CTaX210jvyT7wyOf7mpLlTKfbBBaeYTRHPXnCfJhmS4V3X040bgAi9P-eVk8mbnYhtgOvsN/s692/Chris+Eakin+has+not+said+sorry+for+blaming+Ian+Tomlinson.png)

![The real message from the demonstration is that Big Business must go! Say No to Big Business [4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgcNLHwSXDuZaOjSoMB-UDkHtRf6qEQw-DwuFym02PafUkKC35cOm8wwW0Z1fvN5EkEIoFZFaydCJreW5qHaho3HxSuHrBc2KGPTQJSNRA4q4EH_laOO_wRfimu9MqtH-A7nx76vjsDHe0d/s692/AADHIKAROnline+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+London+Commentary+0300+GMT+27+March+2011.jpg)

![With BOTH EDS BACKING CUTS, what was the point of the staged anti-cuts rally at Hyde Park? [3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiVorOrKw_eb-DQ1Bg3-n82zLZ2rcZpiXLdxVbafVaIGDdyv8r3arDQ4K22XlA2-WTzlAJ7WWbyMzgdwRtLwKbNNmRmLGj3CiVlukz-BMcUe5_CcHjdHYSPBvDbnvlUUiLIxyljKUoE3vix/s150/AADHIKAROnline+monitored+BBC+TV+broadcasting++this+at+2250+GMT+Sat+26+March+2011+Trafalgar+Square+London.jpg)

![No CUTS demo: what happens AFTER the massive turnout? Has either of the Eds the answer ? [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhe2Xnj2gcR4F_0c8BOq45iDHznverk5C-w7Top45-DXYqxp6C_YDaYU91e6qKY3flViykXG35wW09WJ4fwC5vBpBGtEFGc3RY_84x_Yhhq0kZphNk_L5l9gFHpcjPe5WbEs8YKBVSaMxgE/s692/CPGB%2527s+Morning+Scar+at+last+admits+that+Kitty+has+been+dodgy+all+along.png)

![David Cameron is [NOT pictured] complacent about crime in the community. On the world market](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEirxqKdSn2O-qZXQWgVomPvsmXTrfcYG-8V8PXFz-zHZ_m030sZWtLbr56Ip7U3qbX6Zvn_AlxQaO3EUe7ZmWZvkkLVu8QADVhHNd1NsByKtLO_cZAt05ex3HoIG67Yowmayq8IbUrtRDdn/s692/AADHIKARonline+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+London+Commentary+1810+GMT+Thursday+24+March+2011.jpg)

![SUNDAY EXPRESS does NOT believe in the human rights of the involuntarily impoverished!! [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgeTPwVoPLtqfBkw54zmPJSkUSprAub4q5P5Ak3tJhYjy8Td9SXuMEiVGZ2ePmGkdgR9UMYg8mZJvUiGlTgE0ZY-fTu7-zSIQQAe1LJKTsPgAetQ8A2eMroUNx0eW7DructbfjI11Ea8Gr8/s692/15956110.jpeg)

![KEY POINTS of the EAST LONDON COMMUNITY CHARTER AGAINST THE CONDEM CUTS AGENDA [CCACCA]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhvIs5BA4s2LEmg7QJTO8qfJmjWSWT4lXa-8KxKD7bHo5oJkJiDuj9cFIcl0R4i2C0sl5kHt7Dz8eLmT8YFdbbIBqAYmw-9zBBgM2QwqY86LOykVIqrK46fcXCFADu5k2n0_pMQl-Xp2zDs/s692/15953870.jpeg)

![Axeman Alexander [Danny] exposed with biting his tongue when quizzed on his cuts!](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgKesSVRP3davrAT_FlFAcPokL3KJJ7kLq1mfxjl1QBsMe7T1nx7KPJOszax6Xqj4K7TbnK23hC4HEJ-tZjVi-x760Z-Bd0YVDbh88zWTE1HbURMJ1kcHav2rYDgEkOfMAqFiyddkV-oJzF/s692/AADHIKARonline+%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+diagnosing+axeman+Danny+A+13+March+2011.png)

![What wrongful words from the Book of Careerist Opportunism were being transferred there? [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgjiCQDmtMxrIs10LRAVLay0RkHDVlI8fpEAJU46wi9q87QJia-j9C8puUnTYoHpLCoBpSNDqKh1yGAcmQ0Hh4sDApBFl7dqx_cp1wLhrxyz_yMXxkxQcCIshxaR5gLtcIlsvjIZ_AJ-gL7/s692/%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+picture+%255BLutfur%252C+MotinUZamman%252C+Steve+Bullock.png)

![Brick Lane Community + Business: Environment is being damaged, Council is failing [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh_-PvomLvjH5qikIGM2UEwt7BVX3HECyooIqIMX1M2GWs3lwbNK0LqJYk8ijbH64KsaPr0yJvPjzpCuwzUGz5CiIDJUOt3C3ZvCBVvZe57chNHI0UoY7b7NgIq8GbpmnzKngsT9B9VGQuq/s692/%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+London+Reports+Monday+07+March+2011.png)

![Brick Lane Curry restaurant touting. The Truth [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiaQurKBl1-l96TctWTqCtrsem6wML7MJ4CDWK3qTj0rOOwc92nLWN32J1HT7KUwWrru0fkDg51eCSKbKtWLo1omXcnrjdh2SXKLIVWR9VH-Ovx2GEdf-HkmqbjnHwwdqOSA2CH_4wDkSaL/s692/AADHIKARonline+excluysive+investigation+into+Curry+Restaurant+touting+in+Brick+Lane.+Askir+Miah+Sunday+06+March+2011.jpg)

![Examing the problem of touting in the Curry restaurants parts of Brick Lane [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgw7qXUs-_DAySp3xG7oS3syvWiMrhCQh6k0vv12wCYbBeMXReZR8yEL5mLeAKGbHw8Twb9EldFituTKgxQF4S4Txdi8lZOuOu0ss5_lenKxPaMd4jmxEP1hGMIbJxbmdIE4HSudU5X7Npp/s692/AADHIKARonline+Video+report+on+CURRY+TOUTING+.png)

![CAMERON uses ‘Toynbee Hall’ in London E1 as a Weapon of Mass Starvation [WMS]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh3tWw85KoKf46zq9nKxdiZnjUI2YrCuLun0_7LsWZGzZVahyx5Z3n-F6tiFKcqbCH-FcNeAsudb5o54dfwswFtUo7RTLrIdm4B0XaV4BEi-p-AmKiRsu-8tu1b3QHQzERKQb3plXYkaI5k/s692/CAMERON+uses+%25E2%2580%2598Toynbee+Hall%25E2%2580%2599+in+London+E1+as+WMS.png)

![Munich Dave Cameron is following clearly Right path of enemies of Society [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh3JxzI8Ujd1jcz_RIoZ0W2rYmDt62ZGd-5b7X4FJu-pREj-RXyM0cplh5QLqn-0InILCkRzhyphenhyphenBrOJuv_0JOr1bYRiawa0aexZPPbWDtbIhai93_B_xR-2KCwZHjX8KqAKSX9lu0-dUiQiK/s692/15923406.jpg)

![Seelotee people must be treated with a little more recognition than as mere sources of 'Dollar" [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj-Av-hvszg5t5DtqlUCmCqxogjsk_16cFyKDGZL4yocc1NMf6dYpbmFTzADFwYMwYYLv1gHcpC6E2q8iA4nEt2E9VgU8fz_zCJ1scm48Bh7UxbioKdhn5fzwai819YZG6GkKJFkb66R_Wz/s226/15994064.jpeg)

![The Power of the Old! The Lansburys race way ahead of today's 'young' 'leaders' [2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQp6XMPEF215sYFip2UY6YA4TAVTOT2UgKHZLSQuqM0Iyn4MPgXAq1EnwdzthIY97JES2vBXrAhTNQPnkkKZYBJsCbHheEr5M2UZkCz1JwZMWIVYhGs_DnQ-SuXgIlieFxOg0Dzlh6eHPD/s226/%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+montage+%2526+the+pictures+of+Angela+Lansbury+and+the+plaque+she++unveild+in+memory+of+her+grandfather+George+Lansbury%252C+Bow+Church+memorial+event++%255B1400+GMT%255D+%252C+Bow+Road%252C+London+E3.++Saturday+07+May+2011.png)

![They don't have councillors like THOSE ion the East End any more! The Poplar Councillors 1921 [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjj6K-Dal5xwR5P3mJb2CKSgHuESYwCIhcgZ6XQuOwjIJlf2CLaJm9WhtjP3-eHgaToGItPKfE93HW5KXLOF0ySeCgDcW7cQfjNlX4dGBl2E0Wws1pVG1dGChe7H2mzNd_FU90jcWQ7qW8i/s226/Guilty+of+fighting+for+the+East+End+community%2521+And+proud+of+defying+the+rich+and+the+wealthy%2521+%255B1%255D.jpeg)

![Race, ethnicity, poverty and human rights in inner city East End of London: Face the facts [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgITK1B7oCMKPbP3CdIibTChgmcD_5shGc1mYQzFmfRI7R3ug8jzupPfeyaALN-RT1l1XeDA61yuvHwpvzOlawtxTDWVB96OQ2sbScqwnOr16fZMF2SesTmcMeqtXmlikpb6K3wyIqat2mB/s226/STARK+warning+hidden+in+the+figures+must+not+be+denied.+But+the+BBC+and+the+UK+Govt+are+in+denial.+AADHIKARonline+London+Commentary+08+April+2011.jpg)

![Boris takes a risky step to unsettle Cameron AND [Boris hopes] stop Ken Livingstone in HIS tracks](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiNlY4Wbz2soZyR3cqfehmkRHFC8eBrxuyHCgNjB8aeFON246NboD7s_CDaooWJJ_wg0Ez9gAvKaItoSIllF3nGtXi_ZPywOU8ihKiGQs8Yj9UpQb9itm0jLGBDEeyfqKG39Mh-FpvE79A1/s226/15963945.jpeg)

![EAST LONDON COMMUNITY CHARTER AGAINST THE CONDEM CUTS AGENDA [CCACCA] is for the AUDITING MPs +](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg5ljQV10UkhO-Odu-D6cg9vBEtZpTSLaf90z8duDv-ZZrDiWP_IXYyym4FddX5z5Mrn8rrpUD_lKresBdSeWwQjH5xl-Iz2PeMK06Yf9237peu_8PjnT8MEM5YBwA5lBjKiIB0KN6-y_Wi/s226/15953871-1.jpeg)

![Tower Hamlets Council was turned in to a sort of Stockade on Tuesday night [08 March 2011]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEirr10kju7-UDtpzK52ydpkvlkBwPv55O1mpwcWT0SoIbF9Is40wzjbxNGpB4hph1Ahg_l8NKSK-CY6895cp_gm4o7FFntcf_iRlbVFTI3z8yX9-eSrp5Lr68SGb7ItDQMjib6P0UuxHPiI/s226/%25C2%25A9+Muhammad+Haque+London+Reports+09+March+2011.jpg)

5 Comments

Excellent. Great decision. Why on earth does London have this nonsensical policy to dump people on benefits in the middle of affluent areas in the fantasy that the wealth will somehow rub off on the poor? It beggars belief.

The precise reason that canary wharf does not have a sense of community (as councillor Peter Golds alludes to) is because of the ridiculous idea to mix these residential developments. It is why middle class families do not see canary wharf as a realistic place to live. The simple fact is they do not want to be rubbing shoulders with unemployed people on benefits.

I live in the canary central development which in itself is full of pleasant hard working people. However, TH council forced the developers to build social housing right next door in a bizarre effort to mix the community. What we now have is some people working incredibly hard to buy a 2 bed flat for £400k, whilst next door someone on benefits gets it for free. We also have a terrible problem with dog mess from dog owners within the social housing site next door and rowdy anti-social teenagers.

The idea of social inclusion is bonkers!! The two parts of the development NEVER interact. Furthermore, any young middle class families are forced to leave the isle of dogs when their kids reach schooling age because the schools are full of children from parents on benefits.

It really is a tragic state of affairs and unless it is changed, CW will never become a stable, safe and pleasant residential area. Sticking the social housing developments right next to the private developments offers no benefit to either cohort.

Completely agree with Steve Arnold. Why on Earth these people are able to be on benefits and given houses or flats to live in within exclusive areas is hard to fathom. People work all their lives to afford these properties and if people choose not to work then the choice should be made for them by making the houses available to them in areas outside of London.

Both of you appear to be of the misinformed opinion that everyone in Social Housing is on benefits. Little do you realise that any number of the future owners of these properties could let them out to private renters who... then claim Housing Benefit.

You appear to live in a black and white world where you can either afford a £400k flat, or alternatively, you are on benefits.

Where are young people supposed to live, the old, the hard working low paid?

Your arguments are ill thought through, terribly prejudiced and although I am not saying there is not some merit in the discussion, your base assumptions and ignorance is quite disgraceful.

Mike and Steve - your comments are hilariously outrageous and unbelievably ignorant. I would challenge you as to whether you genuinely believe what you're writing, but shamefully I've heard other similar narrow minded comments from others living in the so-called more "exclusive" areas of the Isle of Dogs. I also doubt you could qualify them with anything even remotely sound, besides annecdotes of yobs outside your house.

You do realise that the Isle of Dogs and the wider area surrounding it already had residents before all the glossy towers started popping up. Presumably you are suggesting those that have lived here all their lives are fair game when it comes to developers pricing them and their children out of the area - both in terms buying and rental.

Granted we live in a largely capitalist market, but we are also supposed to be a civilised and developed country where decisions on development need not solely be focused on money, greed and ignorance - which seems to be the principles you value your existence by, which is fine, because to be honest, you're probably in the minority.

i agree w the first comment, why do the councillors think that people on benifits and low incomes can afford to live in that area anyway? its crazy to think people will get their benifits on a monday morning and then stroll into cabot circus to buy their groceries?